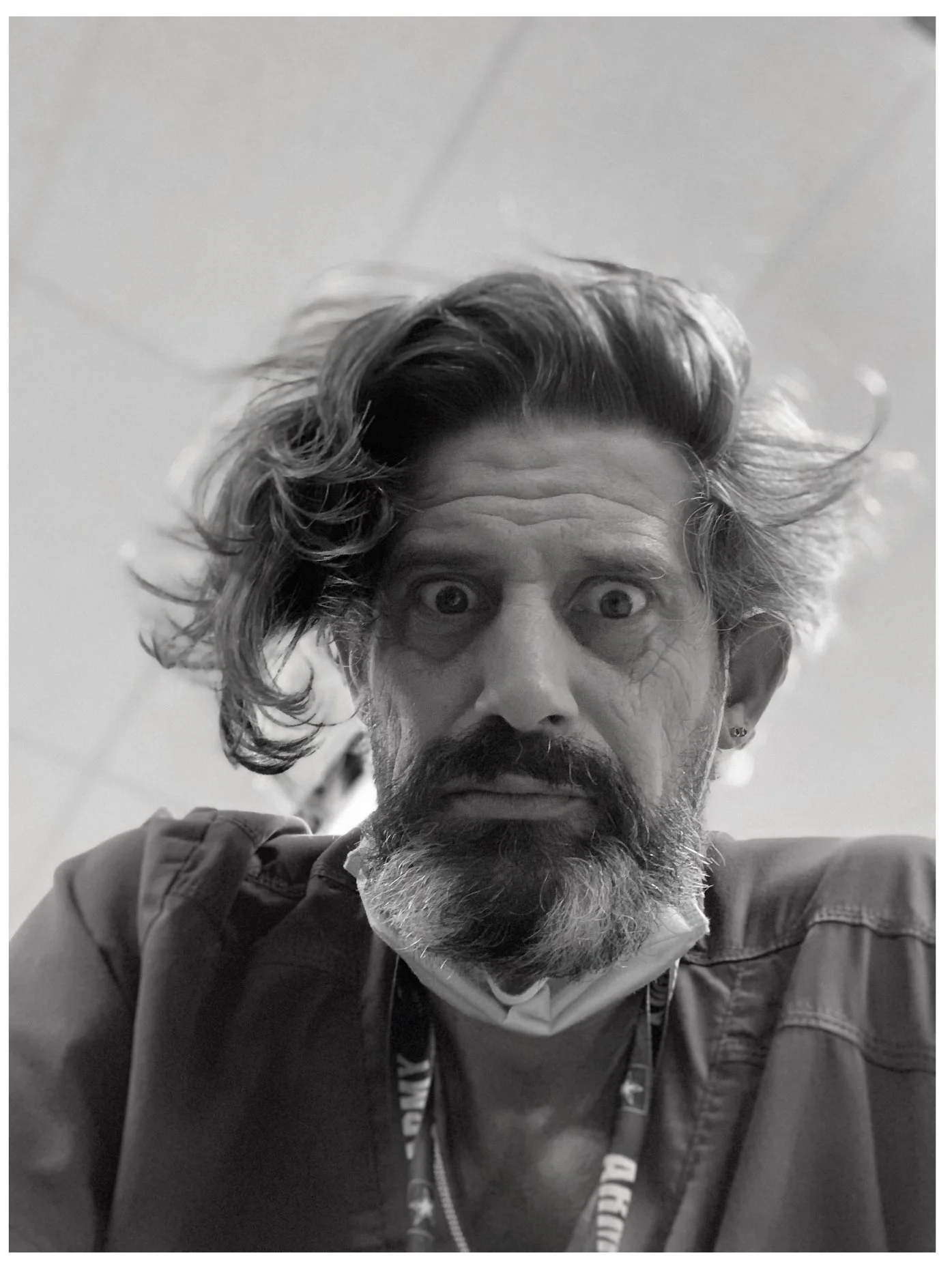

Who I Am — James. No Scrubs. No Jargon. Just UnMedical.

By James Adams

For twenty years, I wore the scrubs.

I moved through the medical world as a CNA, Med Aide, and LVN—working the trenches of assisted living, nursing homes, rehab units, and home health. I didn’t last long in pediatrics, and I thank God every day for the people who do. I even spent a stretch riding house to house on a Harley, checking blood sugars and helping with ADLs. I thought it was funny. The grandmas did too.

But like my time in the Army, I never felt a calling to the profession of nursing. Life’s course somehow led me there. I did the work, and I did it well, but it was never who I was.

I’ve always been a writer. An artist. A musician. A guy with tattoos and notebooks and songs half-finished at 3 a.m. For two decades, I learned how to function inside systems that quietly ask you to sand yourself down. Protocols over people. Filters over humanity. I wore the mask. I showed up. I earned my place.

In 2012, I was awarded the Audie Murphy VA Preceptor of the Year. I’ve earned two hospital challenge coins—most people don’t get one. I trained nurses I still respect deeply and worked alongside physicians and specialists doing extraordinary work, many of whom I knew as residents and later watched become some of the finest healers in the country.

In 2023, I co-wrote a song with pro writers from Nashville as part of The Way Back—an album created by veteran nurses in the VA system telling real stories from the bedside. My track was number thirteen: “Blessed by My Career.”

(I wanted to call it Glutton for Punishment. It got a laugh. I was outvoted. The title, not the theme.)

I mention the accolades not to brag, but to establish the baseline: credibility matters. I know the system because I helped build it. And it’s exactly that experience that allowed me to see where the system fails.

Before: Young nurse. Doing the job. Missing the mission.

Burnout Isn’t a Personal Failure

I spent most of my career on a spinal cord injury unit. My job wasn’t just the nursing side of things. A large part of it was teaching people and their families how to survive once they went home, and how to function when life didn’t look anything like it did before.

One casual conversation with a rehab patient about my age changed everything. He told me how grateful he was for months of demanding inpatient rehab. His mother’s friend’s son had sustained a nearly identical injury but was discharged after only weeks, and suddenly expected to manage complex, high-level care at home with little to no preparation.

In the VA, we did everything we could to set our guys up for success, and the system allowed us to do that. These men had signed a blank check with their lives, and because of that, a real safety net existed.

I didn’t realize how rare that was. I had spent most of my career inside that world and was ignorant to how abruptly care drops off outside it—where insurance, circumstance, and finances decide what help is available, if any.

That was foreign to me. I had lived the majority of my career inside specialty care. I didn’t realize how abruptly the safety net disappeared for everyone else.

That was the gap I couldn’t unsee.

It was horrifying, and it set me into motion. I started writing a book to help families caring for someone with a spinal cord injury. Then I realized something else: people with SCI are living longer now, long enough to develop the same chronic, progressive conditions as everyone else. The book kept growing. The scope widened.

And somewhere along the way, I started burning out.

Not because I was bad at my job.

I loved my team. People weren’t just patients, and some had even known me since I was a student nurse. We grew older together. Most days felt like caring for friends.

That distinction eventually broke me.

Not because I didn’t care.

Because I cared too much, for too long, inside a system that doesn’t slow down for cumulative trauma.

Burnout crept in through the small things:

The constant fear of a Foley being pulled during transfers

A wound that started from one imperfect transfer

The pressure of a med or documentation error

Watching younger patients lose futures they hadn’t even started yet

Seeing men bedbound for months, away from their families, while I still got to go home—even if only for a shower and a nap before doing it again

Vacations didn’t reset it. Time off didn’t touch it.

So if a guy like me—experienced, awarded, respected, paid well, with great benefits and a job I was successful at could hit a wall, it can happen to anyone. Burnout does not discriminate. People aren’t machines, and even machines break down.

The Calling I Didn’t Expect: The UnMedical Caregiver

Like my time in the military as a cavalry scout, I never felt a calling to the profession of nursing. Sometimes I think those paths existed so I could later write songs and stories about what I lived. What I do have is a deep, visceral calling for caregivers.

The unpaid, untrained family members and friends who become caregivers because life doesn’t ask permission first.

When someone is discharged, hospitals hand families a stack of paperwork and a polite “good luck.” Everyone gets the same label: caregiver. It covers everyone from a seasoned RN to a terrified spouse whose life just changed overnight.

That label is too broad. It’s useless.

So I’m coining a new one: The UnMedical Caregiver.

The one with no HR department.

No backup shift.

No benefits.

Just a human being holding a life together with duct tape and sheer will at 3:00 a.m.

I watched these people deliver nursing-grade care at home—often better than anyone gives them credit for. They are the story that begins when the hospital story ends.

Why I Built UnMedical

UnMedical is my last thank-you, and my goodbye to the medical world.

It’s me retiring the scrubs so I can finally be who I am: a writer, an artist, and the guy building a bridge between the hospital and the home—the black hole we all know exists but can’t solve from inside the system.

What puts a person back in the hospital is often common and preventable—missed early signs of a UTI, skin breakdown before it becomes a wound, or subtle shifts in someone’s baseline. My goal is to teach caregivers to see these changes objectively, creating a shared system that improves communication, and the quality of life for professionals, caregivers, and the people they care for.

But that’s not even what breaks the caregivers and family members.

What breaks them is the burnout that never stops.

The family conflict that makes every day a negotiation.

The legal blind spots that turn every decision into a gamble.

The emotional toll of watching someone you love decline while trying to remember if you gave the meds.

So I scrapped the manual and wrote a survival guide instead.

A 350 page straight-talk resource written in simple language so it reads like a conversation, not med-speak

A 28-page “Command Center” binder to turn chaos into rhythm

Tools for progressive conditions, family dynamics, and sustainability

Practical skills—no jargon, no performative professionalism

The “Clown” in the Room

I know I don’t look like what people expect.

Tattoos. Headbands. Boots. Jeans.

More Harlem Globetrotter than NBA suit.

Cpt. Caveman on break.

I was recently asked why I don’t wear scrubs when I speak to caregiver groups because it would make me look more credible. My answer is simple: after everything I’ve done at the bedside, my credibility doesn’t come from a polyester blend. It comes from the miles I’ve walked in those halls. I’m not a faceless organization. I’m not AARP. I’m not the Red Cross. I’m a guy who’s cleaned the mess, lived the pressure, and still kept his soul. I own a suit. I clean up fine.

I’m just more likely to wear it on a stage, along with a guitar, behind a mic.

UnMedical is the bridge from the highly skilled professionals I respect deeply to the unpaid, untrained families who need us most.

For the caregivers who feel invisible.

For the clinicians who already know this gap exists.

For the people we’ll all be someday—at the mercy of someone else’s care.

Let’s make the chaos a little less brutal, one UnMedical step at a time.

I hope you, your family, and your person are happy, healthy, loved, and safe. And remember — if a clown like me can do it, you’ll be fine (if not better).

The UnMedical Guy

Former bedside nurse. Writer. Artist.

Still a glutton for punishment.

After: No scrubs. Found the mission.

Disclaimer: I am not writing this from the perspective of a medical professional. The information in this article is for general caregiver support and educational purposes only. It should not be taken as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider with questions about your loved one’s health or recovery.James Adams